100 Days in the Mojave

Edited by John A. Buchholz

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", August 2001, page 5

April - July, 1929

The Memories of Lester L. Buchholz (1908-1991)

In 1928, with a tent, some pots and pans, six spare tires and two mandolins,

my father, then 20, and his brother John, 25 - both unemployed - struck out from

Geneva, New York, in a Model T Ford to find work in Florida.

But their search

was futile. Near-destitute, they headed west along the Gulf of Mexico, looking

in vain for work at every stop. Finally, after reaching California, they found

employment with Pacific Telephone - my uncle hanging cable in San Pedro, my

father digging holes and setting poles for the first telephone line to cross the

Mojave Desert between Barstow and Las Vegas.

The following account of my father's days in the Mojave is drawn from his 1929 diary and memories audiotaped during

his later years.

John Buchholz

Lester L. Buchholz, c. 1928

I was working for the Robson Seed Farms in Hall, New York, in 1928, and was

laid off in the fall. My brother John had been laid off from his job, too, so he

said, "Let's go to Florida."

"I don't know," I said.

"We haven't got much money."

But I sold my car, a beautiful little

1925 roadster, and we started out on November 24th in John's 1923 Ford coupe. We

had a tent, some cooking utensils, six spare tires, and two mandolins.

We

thought we would find work in St. Petersburg, Florida, so after stopping to

visit our aunt and uncle, who were there for the winter, we rented a room.

But

after three weeks we still hadn't found jobs, and we got discouraged. So we

thought, well, let's take off along the Gulf. We'll just keep going until we find work.

The only place we

had an opportunity was when we reached El Paso, Texas. Somebody had advertised

for Fuller Brush salesmen, but it was somewhere about eighty miles up in the

hills. We decided we'd better keep on going.

But before we went on, we drove

across the border into Juarez, Mexico. We didn't have much money left - very

little - and we got into a poker game. It was a big stakes game - table stakes.

You could bet anything you had in front of you and take that portion of the pot

if you won it. We did pretty well at first. I think we made twenty-five or

thirty dollars right away. But I didn't understand the table stakes part of it

very well, so after a while I lost everything.

Anyway, John had made some money,

and on our way out, we went through the bar. Somebody out there had won some big

money at the roulette table and was buying drinks for everybody. So we had a

couple of drinks and then decided to go back and gamble some more.

And we went

broke. I think we had $1.22 left. Something like that. It cost us $1.20 to wire

our brother Larry for money - any amount he could send us to keep us going.

We

haunted the telegraph office for I think two days before the money got to us.

Larry sent us fifty dollars, and that gave us enough to go on from El Paso.

During the next two days, we drove something like 800 miles. It was a long trek;

a long way for a car that would only do 35 miles an hour on those roads, and we

wound up late at night in San Diego, California.

We stopped at a hotel and got a

room, and we were very, very tired and just about ready to go to sleep when a

rap came on the door.

John said, "You're on the outside of the bed, you get

it."

I went to the door and opened it, and there stood the hotel manager

with two policemen, and they started questioning us. Somebody driving a Model T

like ours had held up a gas station, and the policemen were checking up on us

because they had seen our car parked across the street.

We finally convinced

them that we weren't the culprits, but it was a scary experience. That was one

of the highlights of our stay in San Diego.

After a week of looking for work and

visiting the San Diego Zoo about every day, we went up to Los Angeles. We stayed

at the El Rey Hotel, and as I remember, the rates were three dollars a

day. In order to keep going, we pawned John's mandolin, most of our cooking

utensils, and I can't remember what else.

Our cousin Bill Rigby was in Van Nuys,

so we looked him up and he gave us a few days' work potting roses at his

in-laws' nursery. He had several children, three or four, and we spent more time playing with them

than we did working. But we worked four days at four dollars a day each, so we

had thirty-two dollars. That was enough to keep us for a while.

In the meantime,

we had applied for work at the Pacific Telephone Company. I had worked on the

Lehigh Valley Railroad as a ground hand after I got out of high school, and John

had been a lineman, so we had experience. A month later, on Monday, March 11,

just as our money was running out, they hired John as a lineman in San Pedro.

I

haunted that telephone company for the next two weeks. Somehow I had heard that

they were going to put a line up across the Mojave Desert to Las Vegas. Every

day I'd go up there and talk to the personnel director. I told him I had worked

for the Lehigh Valley Railroad as a ground hand and had done some climbing, but

he seemed to be concerned that I wouldn't be able to take the heat on the

desert.

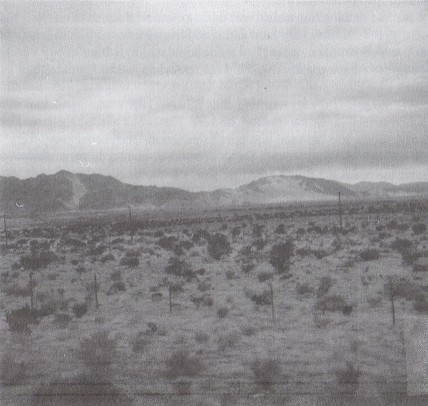

Fence posts and telephone poles cross the Mojave

between Barstow and Baker,

California, 1985.

"Anybody that can work on the railroad in the summer can stand it

on the desert," I told him. "If there's any place hotter than the

railroad in the summer, I want to know where it is."

He finally took my word for it, and

I got the job. There were about 120 fellows in the gang, and they came from all

over the country. The telephone company paid our transportation out to the

desert. We went by train on Sunday night, April 7, and landed out there at a

railroad station in a place called Yermo, very close to Barstow, where they put

us up in camp cars along the Union Pacific tracks.

The first day I did nothing

but dig holes with a shovel, a spoon and an eight-foot, forty-pound crowbar. The

bar had a point on one end and a flat spade shape on the other. It was easy

digging, but the first work I had done since November. It was cloudy and the

wind blew all day, and I had to work with a coat on to be comfortable.

John had

made a little money by that time, and had given me... I think it was three and a

half dollars. But I lost my wallet my first day on the job. The boss and I went

back out to where I had worked that day, but we couldn't find it, so I was broke

again. I never knew if I had actually lost the wallet or if someone had stolen

it.

We had nothing but sandstorms during our first three days on the desert. The

wind blew very hard and sand blew all over and I had it in my eyes every night.

Later, after I had made some money, I tried to buy a pair of goggles -- have

somebody pick them up for me -- but I couldn't get them.

We ate in dining cars

morning and night, and there was a tank car attached to the rear of the line for

showers. The cooks were excellent. They were Mexican, and the food was out of

this world. They fed us very, very well, and would fix up lunches for us, too --

full-course dinners, really -- that we ate under the trucks when we were out on the

desert.

Although we used to get up at 4:30 in the morning and get going, there

was no such thing as a rigid schedule. You'd just get up, eat your breakfast,

and out you'd go.

Some days we would have to drive the truck as many as 45 miles

up into the mountains and canyons. There were other times when we were working

right along the railroad or across dry lake beds that were just as flat as a

piece of cement, and just as hard.

Another fellow and I worked on one hole for

two days out there and got it down only two and a half feet. Digging the adobe

was sometimes that hard ... that difficult. You would hit it with the bar and get

nothing but a puff of dust. The boss finally said, "You can't get it down

any further. All you can do is set the pole in there and pile stones up around

it.

We had very little machinery to work with. There were a few caterpillar

tractors that were used for hauling telephone poles up into the hills, as far as

they would go. And from there we'd have to carry them up into the canyons, sometimes as many as twenty fellows on a pole.

When we were digging

in sand, we couldn't use a mechanical posthole digger or auger, because it would

have pulled the sand out for yards around the hole. So we frequently used what

everybody called "cassoons," but I think they really meant

"caissons" --- two six-foot-long curved steel plates that joined to

form a cylinder. We'd dig a hole as far as we could, until the sand came in

faster than we could dig it out. Then we'd set the caisson into the hole and

climb up on top and spoon the sand out. With our weight on it, the caisson would

ride down into the hole as we dug.

We worked every day of the week. The only

time we had off was for something like five hours one day when they gave us a

course in first aid. Working on a job like that is really hazardous and we had

to know what to do in case somebody got hurt. Fortunately, while I was there,

there were no accidents that I knew of.

The bosses we had were not what you

would call real drivers. They were firm, but they were all very nice fellows. My

boss was from Pennsylvania. George Pet yak. I'll never forget him. He was quite

a guy.

One hole he put me in charge of digging was 12 feet deep, for a 90 foot

pole in the center of a canyon. The line had to go up the mountain, and they

wanted to get it as level as they could across the canyon. Two other fellows and

I dug that hole, and I think it took us two and a half days. We ran into sand

and adobe, and there would be rocks that we'd have to break with the crowbars,

and it was really a tough job. We had to dig a six foot hole first, then dig

another one off to the side to work in. It was the only way we could handle

it, because the bars were only eight feet long.

The crowbars absorbed heat, so

they could never be laid down. We had to stab them in the ground and point them

at the sun so they'd be cool enough to handle.

Our gang used to set the poles,

too. We would dig a number of holes first, and then set the poles and straighten

them up. The boss gave me the job of seeing to it that they were plumb and in

line.

As they moved the camp cars from one place to another, we would have to

dig septic pits, and they would be nearly as big as this room. They'd be

probably twenty feet long and eight feet wide, and they would have to be six

feet deep. I always volunteered to dig them because it paid me a little extra

money. A couple of other fellows worked with me. I didn't mind the work, because

I was used to it.

I can't remember how often I got paid, but I made sixteen and

a half dollars a week, plus board and lodging. I would send my paycheck to John

every time I got one, and he would put it in the bank.

I wore out a pair of

shoes every month, and they had hobnails in them, at that. We would buy a pair

of shoes -- have someone bring them out from one of the villages along the way --

and then we'd have to put our own hobnails in them.

It was a very tough gang, but a very good gang. I never

saw anybody that was the least bit belligerent. We were very compatible. We had

favorite names for some of the guys, names I can't repeat here. But everybody

took it well, you know.

There were tarantulas and scorpions out there, and lots

of rattlesnakes -- sidewinders and diamondbacks. Sometimes we had to kill

rattlesnakes, and they'd be up to six feet long.

There were wild burros out on

the desert that we'd chase down and ride bareback for entertainment. We played

poker just about every night, or shot craps -- one or the other -- and would

wrestle or box every evening.

I remember when we got to Baker, California, about

halfway to the Nevada border. I recall sitting out there in the moonlight, up on

a mountain, you know, and watching the great big moon coming up out of the

desert. Just beautiful. I also remember that they had a big beacon light at

Baker to guide airplanes.

The nights were cool and the days were extremely hot,

and at Baker I saw the temperature go up to 123 in the shade. I wore a pair of

gloves, a hat, a pair of pants, and shoes, and that was about it.

We worked

through the heat of the day, and I always thought that was wrong. But I only

know of two people -- two fellows in the gang -- who passed out from the heat.

Beyond Baker, I can remember little places we would come to -- gas stations

along the way -- that would have slot machines and they'd have beer. But I never

drank anything at all while I was on that job. I stuck pretty close to water,

and plenty of it.

We went nearly out to Las Vegas. The line was, I think, 117

miles long maybe a little bit longer, and we did it in fourteen weeks, from

April 7th to mid-July. So we were putting up better than eight miles a week.

When we came back to Barstow from the other end of the line we were going to go

west from there, maybe into San Bernardino or Riverside or someplace along in

there.

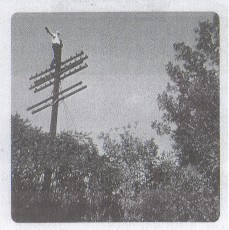

All I was doing at that particular point was putting insulators on poles

that were laying on the ground, and anybody could do that job, so I felt I

wouldn't be needed too much longer. John and I had kept in touch by mail, and we

decided that we would quit our jobs and leave for home on the fifteenth of July.

When I told the boss I was going to leave, he said, "You can't quit."

I said, "I can quit." But he just wouldn't listen to my quitting, and

we went back and forth that way for a while.

Finally he said, "You write

out a request for a leave of absence. You never know, you might want to come

back with us again some day."

I told him that I didn't expect to be back

out there again, but I did write out a request for a leave.

So on Monday night, July 15, Smitty and his

brother drove me to the train and I left for L.A. John and I wanted to get back

in time for our family reunion, so we started out that night. We made it in

seven and a half days.

And that 1923 Ford took us all the way home.

I've always felt that I carried my end of the load out there, or I never

would have been responsible, at that age, for handling a couple of other guys,

digging that 12-foot hole, and aligning the poles.

I learned a lot. I learned

how to get along with people and learned that you had to do your share of the

work. I was always competitive and wanted to do just a little bit better than

anybody else, and do a little more work. I think I averaged around six holes a

day. When I left, I had forty dollars more than I earned while I was out on the

desert. I had made pretty good money playing poker, and had lived on my

winnings, too. I'm not bragging about it. I was just lucky.

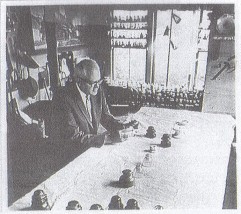

"I was just lucky." 1969

My father began

collecting insulators in the late 1960's and I recall that within the first year

he had accumulated some 250 variations. The centerpiece of his collection was a

beautiful back-lit display he set up in his home near Syracuse, New York.

During

a 1985 trip to California with my mother, my father returned to the desert. He

liked to think that the seasoned old poles he found marching across the Mojave

were some he had helped set fifty-six years before.

John Buchholz

Collecting insulators, 1970.

|